CNC machinists are skilled manufacturing professionals responsible for transforming digital designs into precise physical components. Their work sits at the intersection of mechanical aptitude, programming logic, and process discipline, making them indispensable across high-precision industries. From job shops to large-scale production environments, CNC machinists directly influence throughput, quality, and cost control.

Unlike entry-level machine operators, CNC machinists assume accountability for setup accuracy, tooling strategy, and dimensional integrity. The role requires judgment, not just execution. As manufacturing complexity increases, the distinction between machinists, operators, and programmers continues to sharpen rather than disappear.

What CNC machinists actually do in day-to-day production

CNC machinists oversee far more than machine run time. They interpret technical drawings, translate tolerances into cutting strategies, and ensure machines are producing consistent results across cycles and shifts. Their responsibilities expand or contract depending on shop structure, but accountability for output quality remains constant.

In most environments, CNC machinists handle machine setup, tool selection, workholding configuration, and first-article validation. During production, they monitor tool wear, adjust offsets, and intervene when material behavior or machine conditions drift. When problems arise, machinists are expected to diagnose root causes quickly to avoid scrap or downtime.

CNC machinist versus CNC operator versus CNC programmer

Manufacturing teams often blur titles, but the functional differences matter when planning labor coverage. CNC operators typically focus on loading parts, starting cycles, and performing basic checks. CNC machinists manage setups, complex adjustments, and quality-critical decisions. CNC programmers concentrate on toolpath creation and process optimization, often upstream from the shop floor.

In many facilities, especially smaller shops, machinists wear multiple hats. They may perform light programming edits, modify feeds and speeds, or troubleshoot CAM-generated code at the machine. This hybrid reality increases their value but also raises the bar for hiring and retention.

Core technical skills that define CNC machinists

CNC machinists rely on a combination of technical fluency and hands-on experience. Blueprint reading is foundational, including geometric dimensioning, tolerance interpretation, and surface finish requirements. Measurement competency is equally critical, covering micrometers, calipers, indicators, and inspection routines.

Machine knowledge extends beyond button operation. Machinists understand spindle behavior, tooling limitations, coolant strategies, and material response. They recognize how changes in setup rigidity, tool engagement, or thermal conditions affect part quality. This situational awareness separates reliable machinists from basic machine attendants.

The environments where CNC machinists work

CNC machinists operate in diverse manufacturing settings, each with distinct demands. Job shops emphasize flexibility, quick changeovers, and wide material exposure. Production facilities prioritize consistency, cycle optimization, and volume control. Tool rooms focus on precision, prototyping, and internal support.

Industry context also matters. Aerospace and medical manufacturing impose strict documentation and tolerance discipline. Automotive environments emphasize throughput and process repeatability. Defense and energy sectors often combine both, requiring machinists who are detail-oriented under schedule pressure.

Experience tiers within the CNC machinist workforce

The CNC machinist labor pool is not uniform. Entry-level machinists typically handle simpler setups under supervision. Mid-level machinists manage independent setups, standard materials, and routine troubleshooting. Senior machinists oversee complex multi-axis work, tight tolerances, and process validation.

This stratification affects staffing strategy. Hiring a senior machinist to perform entry-level tasks wastes resources, while assigning complex work to underqualified staff introduces risk. Clear role definition aligns labor cost with operational need.

Why CNC machinists remain in demand despite automation

Automation has changed machining, but it has not removed the need for skilled machinists. CNC machines still require human judgment to manage variability, interpret intent, and resolve exceptions. Automated toolpath generation does not eliminate the physical realities of workholding, vibration, or material inconsistency.

As machines grow more capable, the cost of mistakes rises. This increases reliance on machinists who can prevent problems before they escalate. Automation shifts the machinist’s focus from manual intervention to process stewardship rather than eliminating the role.

Training pathways and practical skill development

CNC machinists enter the workforce through multiple pathways, but skill acquisition remains cumulative and experience-driven. Classroom exposure accelerates foundational knowledge, while shop-floor repetition builds judgment and speed. Employers benefit most when training aligns directly with production realities rather than abstract credentials.

Common entry and advancement pathways

- Shop helper or machine operator transitioning into setup work

- Technical or vocational programs combined with supervised shop experience

- Military or industrial maintenance backgrounds moving into machining roles

- Lateral moves from manual machining into CNC environments

Formal training shortens ramp-up time, but long-term effectiveness depends on exposure to real tolerances, real materials, and real production pressure. Shops that pair structured onboarding with experienced mentorship consistently stabilize machinist performance faster.

CNC machinist skill progression by role maturity

| Skill Area | Entry-Level Machinist | Mid-Level Machinist | Senior CNC Machinist |

| Machine Setup | Assisted or partial | Independent | Complex, multi-axis |

| Blueprint Reading | Basic dimensions | Full tolerance interpretation | GD&T-intensive |

| Tooling Strategy | Predefined tools | Tool selection & offsets | Custom tooling decisions |

| Troubleshooting | Escalates issues | Resolves common faults | Diagnoses root causes |

| Programming Interaction | Minimal edits | Parameter adjustments | Code review & optimization |

| Quality Accountability | First-piece checks | In-process control | Process validation |

This progression clarifies why blanket job descriptions often fail. A “CNC machinist” title can represent vastly different operational value depending on experience depth.

The impact of machinist quality on production outcomes

CNC machinists directly influence production efficiency, scrap rates, and delivery reliability. Small decisions—tool selection, setup alignment, offset management—compound across runs. High-performing machinists reduce variability, stabilize cycle times, and prevent downstream quality escapes.

From a workforce planning perspective, machinist quality affects:

- Machine utilization rates

- Unplanned downtime frequency

- Scrap and rework volume

- Engineering support burden

- Customer delivery confidence

Facilities with strong machinist coverage consistently extract more value from the same equipment footprint.

Multi-axis machining and the rising bar for machinists

As 4-axis and 5-axis machining becomes more common, machinist expectations rise accordingly. These environments compress setup errors into costly failures and demand stronger spatial reasoning. Senior machinists become guardians of both machine safety and part integrity.

Capabilities expected in multi-axis environments

- Understanding of rotational workplanes

- Collision risk awareness

- Advanced workholding strategies

- Tool reach and deflection management

- Coordinated inspection planning

Shops adopting advanced equipment without matching machinist capability often experience prolonged prove-outs and underutilized assets.

CNC machinists in regulated manufacturing environments

Certain industries impose additional demands on machinists beyond dimensional accuracy. Documentation discipline, traceability, and procedural adherence become part of the role. Machinists must balance production speed with compliance rigor.

Industries with elevated machinist accountability

- Aerospace and aviation manufacturing

- Medical device production

- Defense and government contracting

- Energy and critical infrastructure components

In these settings, machinists serve as quality gatekeepers as much as production personnel.

Workforce scalability challenges tied to machinist availability

CNC machinists are not easily interchangeable or rapidly replaceable. Lead times to develop competency limit how quickly shops can scale production. This constraint shapes hiring strategies, overtime usage, and capital deployment decisions.

When machinist availability lags demand, organizations often experience:

- Bottlenecks despite available machines

- Excessive overtime leading to burnout

- Deferred maintenance and setup shortcuts

- Increased reliance on engineering intervention

Strategic workforce planning must account for machinist constraints as a fixed production variable.

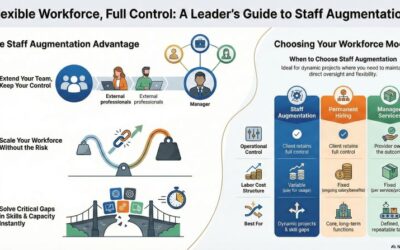

Permanent hiring versus flexible staffing models

Manufacturers increasingly evaluate flexible staffing approaches to manage machinist shortages without long-term headcount risk. Each model carries trade-offs that affect operational stability.

| Staffing Model | Strengths | Limitations |

| Direct Hire | Long-term retention | Slower hiring, higher risk |

| Contract Machinist | Rapid deployment | Variable availability |

| Contract-to-Hire | Skill validation period | Longer conversion timeline |

| Project-Based Staffing | Surge capacity | Limited continuity |

A blended approach often delivers the best balance between stability and responsiveness, particularly for project-driven workloads.

Why vetting CNC machinists requires more than resumes

Paper qualifications rarely reflect real-world machinist capability. Shops that rely solely on resumes or generic interviews often misalign expectations. Practical evaluation remains essential.

Effective machinist vetting methods

- Hands-on setup or test cuts

- Blueprint interpretation exercises

- Tooling and fixture discussions

- Scenario-based troubleshooting questions

These assessments reveal decision-making quality, not just familiarity with terminology.

Retention risks unique to CNC machinists

CNC machinists operate in environments where small frustrations accumulate quickly. Poor machine condition, disorganized tooling, or unclear priorities erode engagement. Retention failures often stem from operational neglect rather than compensation gaps.

Common retention stressors include:

- Chronic overtime without relief

- Inconsistent job routing

- Lack of advancement clarity

- Minimal input on process decisions

Organizations that treat machinists as process partners, not just labor, maintain stronger continuity.

The relationship between machinists and engineering teams

Effective machining operations depend on collaboration between machinists and engineers. When communication breaks down, machinists compensate with workarounds that introduce risk. When alignment exists, manufacturability improves upstream.

Strong machinist–engineering collaboration leads to:

- Faster design feedback cycles

- Reduced revision counts

- Improved tolerance realism

- More predictable production launches

Machinists act as the final interpreters of design intent before material commitment.

CNC machinists and continuous improvement initiatives

Machinists play a central role in continuous improvement, whether formally recognized or not. Their proximity to the process surfaces inefficiencies that data alone cannot reveal.

Improvement areas machinists often influence

- Cycle time reductions

- Tool life optimization

- Setup simplification

- Fixture redesign suggestions

Organizations that actively solicit machinist input accelerate operational learning.

Geographic concentration and regional labor effects

CNC machinist availability varies significantly by region. Manufacturing hubs intensify competition, while rural areas face limited labor pools. Relocation reluctance further constrains mobility.

These regional dynamics impact:

- Wage pressure variability

- Hiring timelines

- Staffing agency reliance

- Training investment decisions

Understanding local labor density is critical when forecasting machinist demand.

Frequently asked questions about CNC machinists

What exactly does a CNC machinist do?

A CNC machinist sets up, runs, and maintains CNC machines while ensuring parts meet precise specifications. The role includes tooling decisions, adjustments, and quality control.

Is a CNC machinist different from a CNC operator?

Yes. Operators typically load parts and run cycles, while machinists manage setups, troubleshoot issues, and ensure dimensional accuracy.

Do CNC machinists need to know programming?

Most machinists do not write full programs but understand and modify code as needed. Programming literacy improves effectiveness and communication.

Are CNC machinists still in demand?

Yes. Skilled machinists remain difficult to replace due to experience requirements and production risk associated with errors.

What industries rely most on CNC machinists?

Aerospace, medical, automotive, defense, energy, and precision manufacturing sectors rely heavily on CNC machinists.

How long does it take to become a skilled CNC machinist?

Competency develops over years of hands-on experience. Training accelerates learning, but judgment matures through repetition.

Why is hiring CNC machinists so challenging?

The role requires technical skill, accountability, and experience that cannot be rapidly scaled or automated.